There's a short bio of Ochagach here. As the bio explains, the route he proposed became essentially a crucial highway to the western parts of Canada used by fur traders. In the French context, it was the fur trade and desire for pelts that drive not only exploration, but settlement and expansion and shaped North America.

Ochagach's map is fascinating to look at and is available in "zoomable" form.

Remember, the first nations of Canada, as far as I know, had no written language or tradition of map-making. This was a person, who from his own mind, was able to prepare a map of Canada beginning at modern day Thunder Bay, Ontario and ending up somewhere beyond Lake Winnipeg, Manitoba. Today, that would be a car ride of over 1,000 KM.

|

| Approximate start and finish points of the original route |

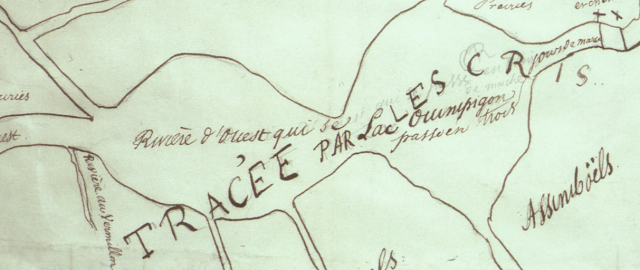

The map shows what appear to be a series of lakes, connected by either short rivers or portages leading ultimately to lake "Ouinipigon" which could be either modern lake Winnipeg or lake Winnipegosis. The various lakes along the route are numbered. I don't know enough about the map to know if these are numbered to help a traveller count how far along they are, or whether it refers to the number of days it takes to reach a certain point.

I've seen the map compared to the map for a subway system in that distances are somewhat reduced and the point of the map is to show a destination and tells you not very much about what goes on between the destinations. In this case, the subway "stops" seem to be the various lakes that you have to count off and traverse to get to where you're going.

There are some fascinating annotations on the map in French that are worth a closer look at.

First, there are details like the ones in this image. Where there is a rare name given to a lake, as opposed to just a number, with an interesting annotation in French: "Lake of Tecacamcouey, of three days of walking". Basically, this map is explaining how long a portage needs to be made to get to this lake.

The image with the name of the destination lake, "Ouinipigon" is also shown with a similar annotation about three days of walking. This image also notes where the Assinibois people live, and says that the map was sketched by the "Cris" or Cree people.

Finally, this image shows the legend of the map. Crosses represent portages. A number of horizontal lines represent large portages, a single vertical line is a short portage and dots are rapids.

There is an interesting, and short article here, in French, about First Nation's cartography. One of the more interesting points it makes, is just how influential First Nations, in general, and Ochagach in particular, was to European map makers. The article cites Ochagach's map as being the necessary information needed by both Philippe Buache and Bellin to complete their maps (images below from Barry Lawrence Ruderman). The influence is clear from just a glance.

|

| Bellin. The annotation in the top left reads, in French "We do not know if in these parts there is land or water" |

|

| Buache |

![1762 map by Thomas Jefferys "A Map of Canada and the North Part of Louisiana with the Adjacent Countrys [sic] This 1762 map by Thomas Jefferys titled: "A Map of Canada and the North Part of Louisiana with the Adjacent Countrys [sic] shows eastern Canada including Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and PEI as well as the great lakes. It has blanks across most of the prairies to the west coast, but does show lake Winnipeg.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiRbsFMD5lEGWOxkh7wTD3Ejy6e9qH2m15dIvVdROWNBDipO748pKgkMmL0gMwbTF12wYnsVx0gzzGzvg5lwjONQxFy_3_sC_grZKSlCDTHhJA3xzymDlKnb40V74mwyNSw3Ajpv7IDDnAo/s640/canada+and+louisiana.PNG)

![1762 map by Thomas Jefferys "A Map of Canada and the North Part of Louisiana with the Adjacent Countrys [sic] An image of the west coast showing a mythological Chinese voyage to North America](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjEsKzzCW7Q2NcGHVZFf44OMc2v7pPQ6QKCDtcugz5pd2LQ2oKTxqit5vXhPjghYPhQNYDqvA4dBhTVXsMb_WQ1amMci1F84TmipIEx-q5zIvc8JaqOf7ADduBNQOqsGpJU9GilFpXCwGpr/s320/fousang.PNG)

![1762 map by Thomas Jefferys "A Map of Canada and the North Part of Louisiana with the Adjacent Countrys [sic] An image of New South Wales in Canada](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj1k5voAdZroAQK7coSRpBLZi_m8fo9zHfOlP7CtxCnaRjg2XXPqsEvOagdaCkwEUI21eGuZS2Z6Y8eH8nUUpGIdbtLm5ncZdIW6P3IBNG1BA-XY-9C79AaqRc4zUkqjhVKRca1vzXw2K3_/s640/odd+things.PNG)

![1762 map by Thomas Jefferys "A Map of Canada and the North Part of Louisiana with the Adjacent Countrys [sic] A detailed portion of the east coast of Canada on the 1762 map](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg2ii2rDN6jpGAbA28GUxAuQimBOVSvsK-J_C0JI_CZAg0SIbI0CbeVyMsGc0J4Badfzr18s5HkR-_WIPpkhrQtKoSGfxn_BT4mEnWUOu8m-DKVbJQ-ptZIUhhDuGG-et-bAknD6gXHXM8n/s640/fade.PNG)